Thinkhubstudio

Dear Partners,

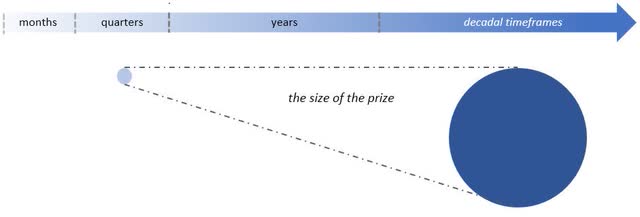

It can be instructive to think of investing prudently as the equivalent of solving a challenging math equation. This analogy can be applied to time, energy or any other limited resource much like capital. In all these cases, the inputs are finite and need to be proficiently optimized subject to which outputs, among several available choices, one is seeking to “solve for”. Using this analogy, allocating capital over a decadal time frame involves optimizing for supremely different output variables relative to the variables that matter over a multi-quarter or one-to-two-year horizon.

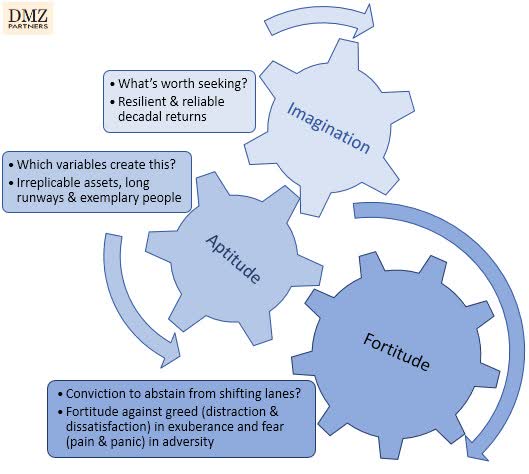

Solving this puzzle involves effort on three fronts – imagination, aptitude and fortitude.

The Upanishads1 are credited with having shed light on this, albeit in a different context:

“You are what your deepest desire is. As is your desire, so is your intention. As is your intention, so is your will. As is your will, so is your deed. As is your deed, so is your destiny.”

Lest this seem too philosophical, I will tie it back to investing, where the rubber meets the road. In this regard, imagination comprises of choosing the appropriate outputs that are worth solving for. Aptitude pertains to adeptly identify the corresponding inputs that hold sway over the chosen outputs. Fortitude involves staying true to the game in times of both, adversity and exuberance alike.

The imagination challenge involves isolating the correct outputs that are worth optimizing. It also involves dispassionately ignoring other “pseudo outputs” that are inconsequential and often wear deceitful cloaks of respectability simply by virtue of being widely acclaimed or frequently cited. The legendary pioneers, across domains, share in an exemplary core capacity – focus. Focus enables the pursuit of a singular goal, which is distilled from an unabashed yet vivid imagination.

While this is often trivialized, the trade-offs implicit in choosing one goal at the expense of all othersisdaunting from the driver’s seat. Although a small subset of investors may be adept at identifying the right outputs, only a rarefied breed of allocators is able to entirely dismiss these pseudo outputs. In reality, these are deceptive and expensive detractors that deviate many from the most favourable of outcomes.

Tangible examples of pseudo outputs for a long-term, business-oriented investor, at a fundamental level, may be monthly unit sales of a portfolio company, and at an investing level, may be quarterly portfolio performance relative to an index. Neither of these are pertinent measurements of true progress for a decadal investor, which should ideally render these metrics close to meaningless.

Quite to the contrary however, such metrics are often maniacally measured and feverishly interpreted at the expense of outputs that are truly worth weighing. This either implies that others around us are likely solving for an entirely different variable or perhaps forgot to stop and ask – Why does this matter?

On the other hand, often measuring what matters risks feeling qualitative, non-rigorous, nonstandardizable, and mushy. Ask the typical analyst what they think of the entrepreneurial culture of a firm or the risk-taking orientation of the founders or the resilience of the firm’s business model in times of unprecedented, long-lasting adversity or the embedded optionality value and non-linearity inherent in the managements or businesses they study and write to me to share the bewilderment you witness!

To be clear, this is not to undermine the efforts of the typical analyst – this is simply to suggest that they are in the business of solving for a very different variable in the investing equation.

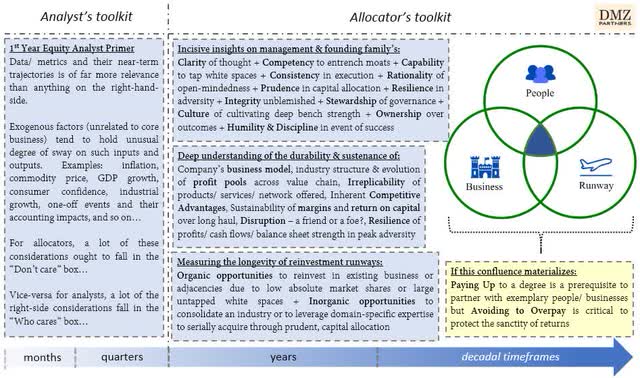

The aptitude challenge involves identifying the input variables that hold the potency to maximize the output variables previously identified. Tomes of research are published regularly on the factors affecting businesses, industries and economies. Their prospects and investment outlooks are meticulously weighed using a multi-quarter or year-ahead lens. Glaringly little, however, is written on what the constituents of a decadal allocator’s toolkit ought to look like.

Ask an analyst for their thoughts on a business and they will inundate you with meticulous analysis of every financial statement metric with estimates going to two decimal places. Ask them if it merits investment and you will likely hear. “I expect upward revisions on 2024-25 earnings expectations from all the sell-side firms in the next 2-3 quarters due to XYZ changes and this is likely to lead to a re-rating of from X to Y 2025E P/E rendering an upside potential of Z%”. For a decadal allocator with a business-owner orientation, this is meaningless noise.

Leaving aside discussions of whether solving for certain variables is fruitful, this isn’t a criticism of any approach as much as it is an elucidation that the variables being solved for by the analyst are entirely different from the variables business-oriented, patient investors ought to focus on. As one would expect, if output variables we are solving for are different, shouldn’t the inputs be different as well?

For example, an analyst assessing the investment merit of a motorcycle business for a 1 year holding horizon will have to expend substantial resources to analyse how key input costs will move over 12 months, what the precise product-mix will be over the next 4 quarters, how the company hedges for currency effects, how clogged the inventory levels are across the supply chain, how monthly sales are trending given the company’s and competitors’ expected near-term product refreshes or launches, whether the labour issue at factory A is likely to resolve by quarter 2 or quarter 3, how the company may change pricing in response to market dynamics in the near future, and other metrics that hold tremendous relevance from a 1-year perspective.

Additionally, they will have to overlay to what extent all these expectations are widely appreciated by the market or implicit in the stock price, basis which they can pass an opinion on whether the stock is undervalued or not from a year-ahead perspective.

Concerningly, I’ve witnessed several investors with access to permanent and patient capital simply “scale up” the analyst toolkit to express their longer time horizons. However, it should be no surprise that this is a flawed approach as the analytical frameworks used by decadal allocators ought to be entirely different from the one’s used by the analyst. Yet one often witnesses, potentially permanent asset owners simply scaling up analysts’ toolkits to reflect their lengthier tenures.

For example, assessing a decade long runway is not the same as projecting the same monthly unit sales time series the analyst assesses and simply taking in more historical data and projecting further ahead over a decade. The underlying variables ought to change almost entirely, as shown in the exhibit above.

The fortitude challenge in its simplest form involves, on the one hand, not getting carried away by seeing everyone doing exceptionally well in asset classes or companies that you have no understanding of in times of extreme exuberance, and on the other hand, not getting dismayed into selling everything to buy the “safest” instruments in the most uncertain times.

While the criticality of fortitude is clearly palpable in the most extreme examples, interestingly, and in my experience, the greatest distractions to steadfastly staying the course arise not in the apparent extremes but in situations “at the margin” or just beyond the edge of the limits of one’s own investing principles.

For example, investing over a decadal horizon often involves (somewhat) knowingly owning assets that may not be the most rewarding over the medium term (say 1-2 years), while recognizing that they hold tremendous promise over a decade. This isn’t a straightforward conundrum, as most investors explicitly or implicitly seek to do well overa year and over a decade.

The problem is that those two variables are often imperceptibly and unknowably at odds with one another – if the first variable holds a mild unspoken sway over one’s psyche, it steadily contributes to chipping away at the unadulterated pursuit of the most important variable in one’s investing equation, which in our case is the focus on doing well over a decade. Zoom out to consider the dozens of such unspoken sub-optimal variables that are chipping away bandwidth from one’s most important investing pursuits.

The rewards of adeptly deploying a multi-decadal framework is perhaps only achievable by a rarefied breed of patient, business-owner oriented investors who have both, the privilege of permanent capital and the discipline to abstain from countless distractions. While many investors swear to such monkhood, their implementation is restricted to the time they are seated in the proverbial calm of Himalayas. However, we can appreciate that investing with emotional fortitude involves retaining the same calm of monkhood while strolling down the Vegas strip at 2 am – a materially different challenge.

Seeking regular reaffirmation is another misplaced sense of thoroughness that investors with weak fortitude seek. I recently met a colleague with access to permanent capital who lamented, “I need X% returns each year, or my money would be better off in the bank.”

Unfortunately, even the most resilient forms of equity investing are incapable of providing such regular reaffirmation. Demanding regular reaffirmation simply provides an illusory ruse of diligence that deviates one further from a business owner orientation. If you’re invested in the business, you ought to think of your “invested capital” as having contributed to a fraction of the shareholders’ equity of the business (even if you bought at a price substantially greater than the company’s book value) rather than thinking of your capital as the number of shares you own multiplied by the share price.

Think of your investment in the company as the founding family would think of theirs – not a squiggly line that moves every day, rather as the company’s equity, which funds people, processes and assets in their pursuit of creating tremendous long-term value.

Even if you’re a relatively recent investor in a longstanding business, while your purchase of a listed share simply relieved another owner of theirs, try thinking of the capital you invested in the listed equity as directly (albeit partially) contributing to the existing aggregate equity of the company (with a premium paid to the seller). Mentally disassociating the listed share from the business is a great disservice for patient investors to commit to themselves.

As we are entrusted with managing patient capital, we are effectively obligated to ensure that we follow an approach that factors as much for the return of the capital as it does for the return on the capital. In our view this is best achieved by partnering with exemplary people who run irreplicable businesses that are blessed with unusually long scalability runways ahead.

This sums up an overview of what we call the investing equation. Lest I seem presumptuous in sharing several nuances of our approach through our letters, please consider that there are several compelling approaches. We’ve simply chosen to commit to an approach that we can consistently implement without getting distracted or losing a good night’s sleep– these parameters ought to form the bedrock for committing to any thoughtfully deliberated principles by individuals, families and institutions.

I remain humbled by your conviction to invest with us and strive to remain worthy of it.

Warmly,

Soumil S. Zaveri | soumil@dmzpartners.in | DMZ Partners

|

This redacted version of our letter has been edited to remove references to investment actions, security specific opinions, information on client-oriented events or other specific references. As a matter of prudence, we prefer not to share certain information so as to minimize the possibility of misinterpretation by a reader. Important Disclaimers: This document is only intended for clients of DMZ Partners Investment Management LLP (DMZ Partners). The contents of this document should not be construed as investment advice. All material stated herein is solely for informational purposes. The contents of this document should not be construed as a solicitation or offer to buy or sell any financial services and/ or financial securities and/ or related financial instruments. DMZ Partners, its partners, and its clients may own shares of companies mentioned herein. Please consult a registered financial advisor prior to making any investment decisions. DMZ Partners, its partners, employees and associates accept no liability for any errors or omissions in the content herein. Unauthorized usage, alteration or distribution of this information is prohibited. Any errors or omissions are regretted. The content provided herein should not be interpreted as claims, projections, guarantees of any financial results or returns. The content provided herein should not be interpreted as forward-looking estimates of the future performance of our investment services, our portfolios or our portfolio companies. Any performance-related data provided herein is not verified by the market regulator, SEBI. |

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment