jetcityimage

It has long been my thesis that Wayfair (NYSE:NYSE:W) was a bubble stock, though I didn’t write publicly on it (instead, it was part of my Idea Generator service). My thesis, more than being based only on Wayfair’s outrageous valuation, was based on other realities:

- Wayfair pursuing a (difficult for most, including Amazon.com) 1P (First-Party) eCommerce business.

- Wayfair’s consistently negative EBITDA margins, and resulting cash burn.

- Wayfair’s negative book value, by a large $1 billion at the time of my thesis.

- Wayfair trying to do fulfillment of the worst possible products — big, bulky items.

- Wayfair not just having negative book value and negative EBITDA, but also a large debt load.

For a while, a lot of this thesis was challenged by the COVID-19 epidemic, which led to the shutdown of offline competitors, at the same time it confined a large part of the population to their homes and fed it large stimulus checks. The result was a rush to buy lots of home furnishing product online.

This passing trend was so powerful that it even allowed Wayfair to temporarily have decent EBITDA margins, in large part due to fixed cost dilution (especially on advertising) due to the extreme demand being served by a lot fewer suppliers (physical competitors were excluded). For a while, the short thesis was quite challenged.

However, that’s all past us now, and as demand for home furnishings (and eCommerce in general) normalizes, it’s perhaps time to re-visit Wayfair. This is even truer today since Wayfair stock has already crashed – Wayfair is down by more than 84% since its high 1.5 years ago. It’s time to try to establish whether Wayfair might now be cheap or whether prospects or my opinion on them might have improved. So, let’s do this.

A New Problem

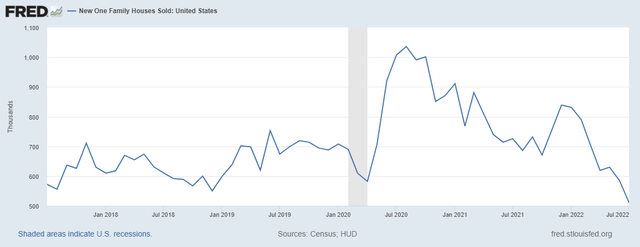

An immediate observation, is that Wayfair now operates in an environment that’s worse than the one existing pre-pandemic. We have higher inflation, which led to higher interest rates, which is now putting pressure on new and existing home sales.

FED New Home Sales (FRED) FED Existing home sales (FRED)

Obviously, home sales are a tremendous driver of home furnishing sales, hence this large (and recent) drop in home sales is set to put tremendous additional pressure on Wayfair.

This is rather unavoidable. In the short-term Wayfair is more or less forced to restructure itself given this factor alone (plus the absence of stimulus and COVID-19 driven demand).

By “restructuring”, here, I mean laying off personnel, reinventing operations, changing operations to increase profitability. In the limit, “restructuring” could go all the way to a debt restructuring – but that is NOT what I am pointing at this moment. I am just saying that this environment is going to force Wayfair to change its operations.

Short-term, everything looks truly ugly for Wayfair, and the stock is reflecting it.

This factor, once again, leads to the (past) bearish thesis. Plunging home sales are likely going to:

- Drive negative EBITDA.

- Drive negative FCF.

- Drive losses and negative equity. It’s to be noticed that Wayfair’s negative equity is now negative by $2 billion, instead of $1 billion pre-COVID, in spite of all the favorable environment Wayfair went through.

It’s as if we’re back to pre-COVID, only worse.

But is there no hope at all? That’s where my other main observation comes…

Is There Hope?

The obvious need for change might lead Wayfair to try something new. And that’s, in my view, the hope I see for Wayfair. This hope also comes from my own reevaluation of Wayfair’s business and prospects.

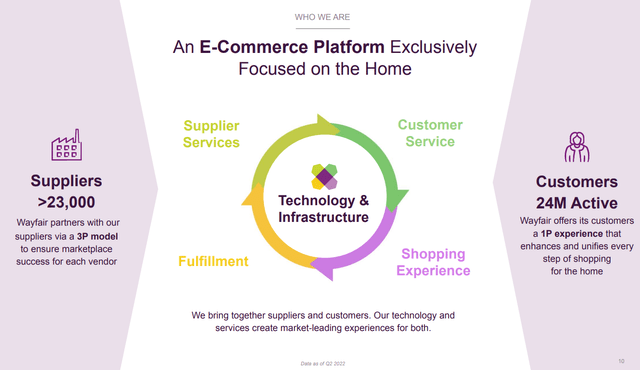

I think since Wayfair has, to some extent, the public’s eye, it also has a shot at turning itself into a 3P marketplace. That is, to turn itself into a marketplace for 3P (Third-Party) suppliers for home improvement and furnishing in general. Wayfair already does this to a small extent, in that it doesn’t carry supplier inventory or, at times, logistics. Typically, as has been shown by Amazon’s 3P marketplace, eBay (EBAY) or Alibaba (BABA), 3P marketplaces can be extremely profitable businesses.

The profitability comes from it being cheap, after having the public’s eye, to just expose the public to products from third-parties, and then taking a (large) cut of each sale while not bearing most of the costs of commerce. In short, the 3P marketplace “just” runs a website showing seller listings, and handles payments. All the remaining costs of servicing the public (logistics, inventory, physical customer service, warranties, competition, etc) fall on the third-party sellers. Due to this, large 3P marketplaces tend to be very profitable businesses.

It Might Be Impossible

I see Wayfair’s main opportunity coming from it possibly turning into a true 3P marketplace. However, there are many reasons to be wary of this potential transformation. For instance:

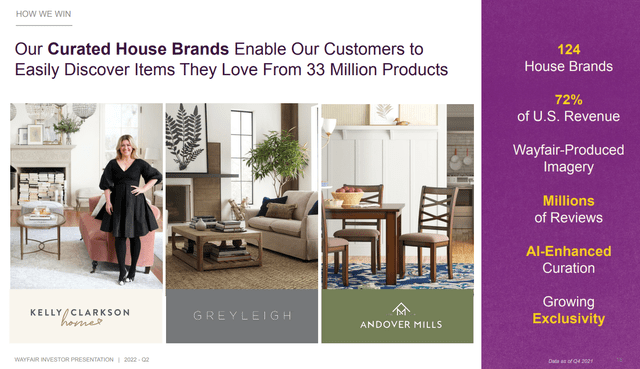

72% of Wayfair’s US revenues comes from its own products. This immediately makes it more of a 1P online furniture retailer than anything else.

It’s hard to see how to avoid this 1P fixation, in the context of the change which needs to happen, for Wayfair to avoid competing in uninteresting businesses. It’s true that this is how Wayfair wins sales and revenues, but not how it might win profits.

The beauty of a 3P marketplace, from the economics standpoint, comes from taking a large cut of a seller’s price, and then having him bear nearly all of the sale costs (sourcing, curation, presentation, customer service, logistics, etc).

We could say that Amazon’s (AMZN) marketplace handles logistics (and at times, customer service). But it didn’t start that way. Instead, it first put all of these costs on the back of sellers, and then, slowly, internalized some functions while being paid for them. This internalizing was not the profit driver — it just worked as another growth driver for the already very profitable marketplace, later.

Here’s What To Look At

eBay is a proper, pure, 3P marketplace. eBay did $10 billion in revenues TTT (Trailing Twelve Months), versus $12.6 billion for Wayfair.

However, eBay’s revenues count only the fees paid by the sellers in its market (including advertising), not the GMV (Gross Merchandise Value) being moved through the marketplace. Wayfair, on the other hand, counts the actual GMV of its sellers, which is why its gross margin percentage is so much lower than eBay’s – 27% for Wayfair over the last 6 months, versus 72% for eBay.

Hence, to make Wayfair truly comparable to what eBay does, we’d have compare eBay’s GMV to Wayfair’s revenues. eBay moved around $80 billion in TTM GMV. Thus, on a comparable basis, eBay is handling 6x more merchandise than Wayfair.

It is now that the true surprise hits: How many workers does eBay have? Around 10,800. And how many for Wayfair, which should be, in practice, doing around 1/6th of the business? 18,000.

Therein lies the problem. As I explained, Wayfair’s biggest chance to turn into a viable, profitable, business is to turn into a true 3P marketplace. And to do so, it needs to drop a lot of the work that it’s now carrying for its sellers. Of course, somewhat worrisome is that the customer experience might well suffer, and the size of the business suffer with it – unless pricing compensates.

What work would be dropped? Things which Wayfair is actually proud of:

- Curation. Wayfair curates products carefully. eBay relies on suppliers to classify and curate products.

- Presentation. Wayfair uses its own workers to present products in the context of collections and so on. eBay relies on suppliers to present products.

- Customer service. Wayfair is proud to handle customer service as if it were a 1P marketplace — that means having its own customer service representatives, with knowledge on millions of products. eBay relies on sellers to provide customer service.

- And so on …

Although Wayfair doesn’t behave entirely as a 1P seller, it does behave to a large extent as a 1P seller. It handles many functions which in a true 3P marketplace would be handled by the third-party sellers, and as a result it bears all the cost associated with those functions. The only way to turn into a profitable 3P marketplace, is to stop handling those functions and bearing those costs.

This is it. For Wayfair, building a true 3P marketplace is the one true thing which I think can make its business be valuable. It has the underpinnings to turn into a real 3P marketplace (customer eyeballs), and it has the urgency to change its business model into a profitable one. But it also faces tremendous difficulties in turning into a 3P marketplace, since the destination is so very different from what Wayfair is today.

Conclusion

Wayfair was a bubble, which got temporarily helped by the COVID-19 pandemic. Right now, Wayfair faces a more challenging environment than even before the pandemic, due to housing being under pressure.

Wayfair has returned to a form where it might even struggle to survive. However, at this point, Wayfair will know that it will have to undergo a significant restructuring in my opinion.

That potential restructuring opens the chance that Wayfair will unlock the only possible value it has: turning into a true 3P marketplace, the kind of which carries good margins. Wayfair has a chance at this because of the number of customers it already attracts to its websites.

Such a change is possible, but it goes against a lot of what Wayfair does today, some of which appeals to customers (the careful curation, the First-Party customer service, etc). Anyway, that’s the one way I see for Wayfair to unlock value – otherwise, its very existence might at some point come under doubt.

For now, in the absence of such transformation Wayfair still looks like a sell to me. Were such a transformation attempted, then I think it would at least be a hold.

Be the first to comment