da-kuk

It’s been a bit over two months since I finally “pulled the trigger” on Trinity Industries Inc. (NYSE:TRN), and in that time the shares have returned about 32.3% against a gain of about 6.4% for the S&P 500. I absolutely love writing about my successes because I’m an inveterate braggart, but I’ve got some serious business to attend to this morning also. The company has released financial results since I last reviewed the name, and those deserve commentary. Additionally, a stock trading at $30.60 is, by definition, a more risky investment than the same stock when it’s trading at $23.50, so I want to decide whether it makes sense to buy more, hold what I’ve got, or “take the money and run.” I’ll make that determination by pouring over the latest financial results, and by looking at the valuation.

I have heard from some people that I’m “good in small doses.” In other words, people are comfortable reading a few hundred of my words, but the luster quickly wears off. Given that, I write a “thesis statement” at the beginning of each of my articles. I do this to minimize your exposure to too much “Doyle mojo.” I also do this for people who want a little bit more than they can get from bullet points, but may not want to commit the full package of 1,600 of my words. You’re welcome. Anyway, I’ll be taking my Trinity chips off the table this morning. I’m doing this because I’m disappointed by the most recent financial results. Specifically, I don’t like the deterioration in the capital structure, and I assumed that they’d have moved closer to the 2019 glory days by now. Additionally, and unsurprisingly, the stock price is much less compelling now. For those reasons, I’m going to take my chips off the table. I may (likely will) miss out on some future upside from current levels, but I’m of the view that it’s better to preserve capital at this point. As I write below, I’m comfortable embracing my cowardice. Finally, I wrote much more extensively about what’s going on at the business in my previous article. Specifically, I wrote about how we should think about the industry given the most recent Greenbrier call, and I wrote about the most recent GATX order. If you’re interested in the details, I’d refer you to that article, but if you’re more of a “Cliffs Notes” kind of person, I came to the conclusion that the GATX order is significant, and I expect it to boost revenue by between 7-10% for the foreseeable future. From the Greenbrier call we learned that demand is picking up across the industry.

Financial Snapshot

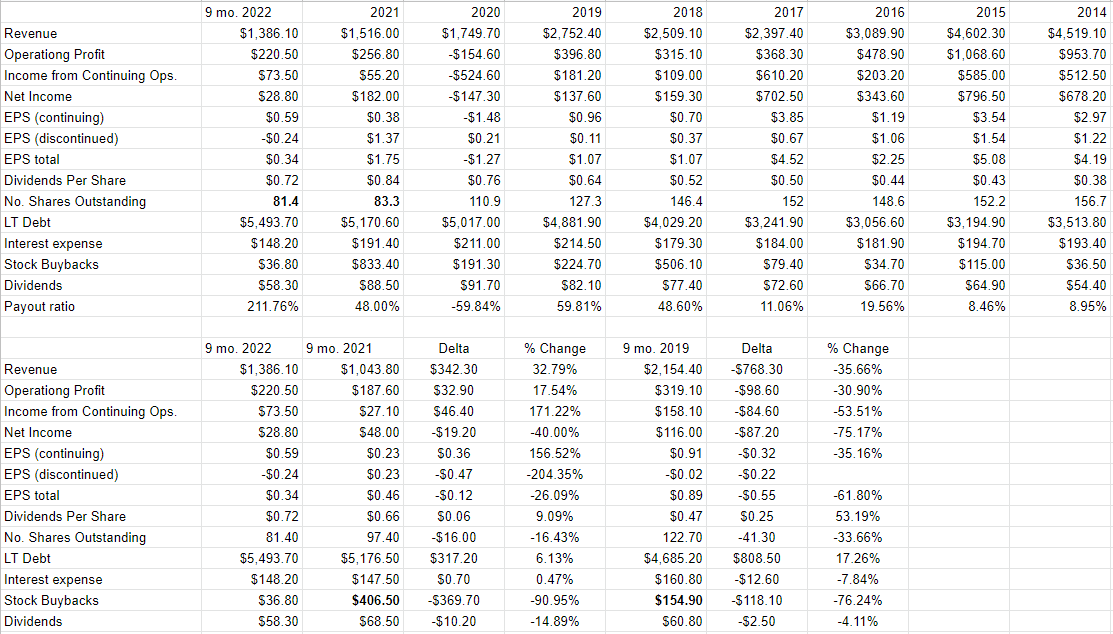

On the surface, it seems that relative to the previous year, the first nine months of 2022 have been quite good in some ways. Specifically, both revenue and income from continuing operations are up by 32.8% and 171% respectively. Additionally, the company has rewarded shareholders with a 9% uptick in the dividend, and, thanks to the buyback, shares outstanding are down a whopping 16.4% from the year ago period. This buyback has been so aggressive that dividends per share have risen, in spite of the fact that the company spent fully $10.2 million less on dividend payments.

If we dig a little bit deeper, though, we see that fully $27.3 million uptick in operating profit came from gains from lease portfolio sales. This represents about 81% of the positive delta from the prior year, and I wouldn’t want to rely on it continuing, no matter how robust the demand for railcars is at the moment. Additionally, last year saw an $11.7 million loss on the extinguishment of debt, which was $10.2 million higher than the current loss on debt extinguishment. Thus, I think we should be skeptical of any claims that the current year is dramatically better than the previous one.

Additionally, I don’t like the fact that the capital structure has deteriorated. Specifically, long term debt has risen by $317 million, or 6.1%. Cash on the balance sheet this time last year was $221.8 million, and it’s now $58.5 million. At some point, the reality of the capital structure and the reality of the business cycle will make ever rising dividends an impossibility.

Finally, I think it would be wise to point out that the financial performance is still way below where it was in 2019. Although the company has become much more efficient, there’s not much proof of that showing up in the financials yet. Revenue and operating income for the first nine months of 2022 are still 35.7% and 75% lower respectively than they were in 2019.

Given all of the above, I’d be happy to hang on to my shares, and even to add to them, but I’d need the stock to be priced very attractively.

Trinity Financials (Trinity investor relations)

The Stock

I’ve just noticed that a larger number of people are following me now for some reason. Welcome, I guess, and thanks for dropping by. Anyway, if you’re a regular, you know that I consider the “company” to be quite distinct from the “stock” because I drone on about it so often. If you’re one of the new people, I consider the stock and the company to be very different things. I may risk tedious repetition by doing this, but I have a proven history of being totally comfortable being tedious. I also think the point is worth repeating because it’s an important one. A great company can be a terrible investment if you overpay for it. A related point is the fact that the stock is often a very poor proxy for the company. The company takes a number of inputs, like various grades of steel, for instance, adds value to them, and sells the results to a lessor or a Class 1 railroad for a profit. The stock, on the other hand, is a traded instrument that reflects the crowd’s long-term views about the strength of the business. Additionally, the stock is affected by a number of variables that have little to do with the business, including changing interest rates, the crowd’s desire to own “stocks” as an asset class etc. In my experience, the only way to profit trading stocks is to spot discrepancies between the crowd’s views and subsequent reality. If the crowd is too pessimistic, for instance, it makes sense to buy and then ride the price higher as new information is eventually digested. If the crowd is too optimistic about a company’s future, it’s best to avoid the name in my view. The level of optimism or pessimism in a stock is reflected in the valuation. If the crowd is optimistic, the shares are not cheap. I absolutely hate to remind all of you of this, but this is how I was able to make such an extraordinary return on my Trinity shares over the past two months. I came to the conclusion that the market was too pessimistic about the company, given what was going on in the cycle, and I took advantage of this discrepancy in price versus expectation.

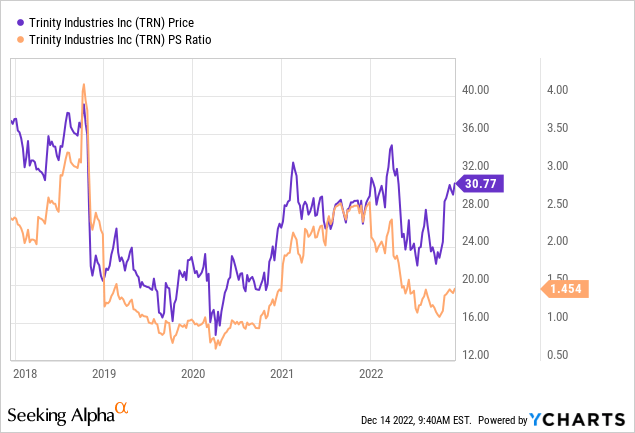

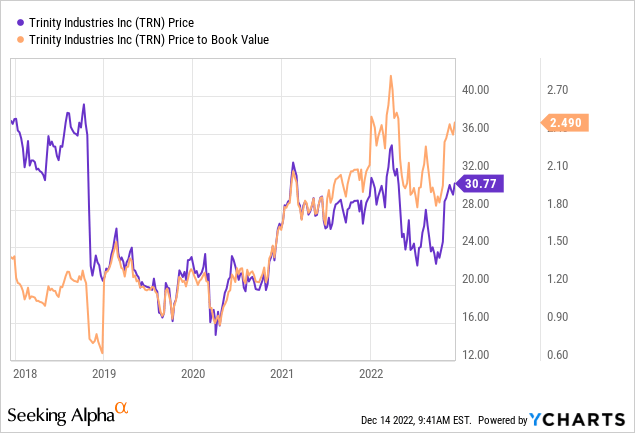

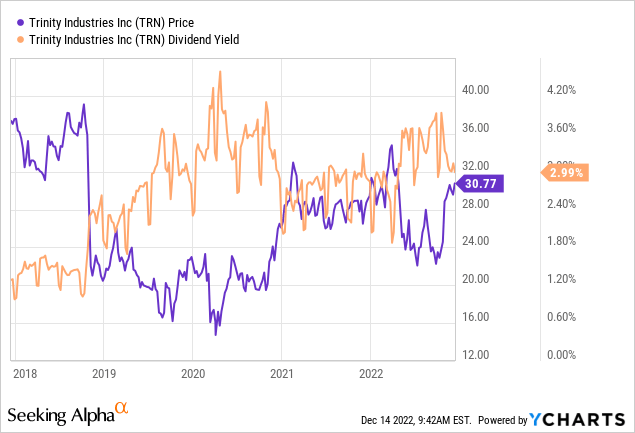

I measure the cheapness (or not) of a stock in a few ways, ranging from the simple to the more complex. On the simple side, I look at the ratio of market price to some measure of economic value, like earnings, sales, and the like. I want to see the shares trading at a discount to both the overall market, and to their own history. In case you don’t have your “Almanac of Doyle’s Trades” in front of you, I’ll remind you that I bought the shares when the market was paying $1.28 for $1 of sales, $1.878 for $1 of book value, and investors were receiving a 3.94% dividend yield. Using the skills of arithmetic not at all lovingly imparted to me by the good sisters at Holy Spirit school many decades ago, I have calculated that the shares are now between 13% and 33% more expensive per the following. Additionally, the dividend yield has collapsed by about 25%, so investors who buy today can expect dramatically less in terms of cash flows going forward. Given my view that the dividend can’t grow continually, I think this is troublesome.

If you know I like cheap stocks, you also know that I want to try to understand what the market is currently “assuming” about the future of a given company. If you read me regularly, you know that I rely on the work of Professor Stephen Penman and his book “Accounting for Value” for this. In this book, Penman walks investors through how they can apply some pretty basic math to a standard finance formula in order to work out what the market is “thinking” about a given company’s future growth. This involves isolating the “g” (growth) variable in this formula. In case you find Penman’s writing a bit dense, you might want to try “Expectations Investing” by Mauboussin and Rappaport. These two have also introduced the idea of using stock price itself as a source of information, and then infer what the market is currently “expecting” about the future.

Anyway, applying this approach to Trinity at the moment suggests the market is assuming that this company will grow earnings at a rate of ~6% in perpetuity, which I think is very optimistic. Given all of the above, I’ll be taking profits in Trinity this morning. I may miss out on some future upside, since the analyst community is quite optimistic here, but I’d rather miss upside than risk capital loss. I’m comfortable in my cowardice.

Be the first to comment